February 9, 2012: The posts on the page below were written during my recent three-week reporting trip to the Maldives, prior to the overthrow of former President Mohamed Nasheed. I have left all the posts as they were originally written. Here’s a link that I didn’t initially include from my interview with Mr. Nasheed. Click here to watch his response to my question about the nation’s political volatility.

_________________________________________________________________

A CONVERSATION WITH MALDIVIAN PRESIDENT MOHAMED NASHEED

I had the opportunity to interview President Nasheed late last year. He reaffirmed his commitment to making the Maldives carbon neutral by 2020 – placing his odds of success at 99%. If his country fails, the #1 culprit – in his words – would be the oil industry. Here’s why. President Nasheed also said plans are moving forward for a “sovereign wealth fund” that would allow the Maldives (or possibly a third party acting on behalf of the Maldives) to buy a plot of land in another country, where Maldivians could reside in case the nation ends up underwater, as many scientists predict.

I had the opportunity to interview President Nasheed late last year. He reaffirmed his commitment to making the Maldives carbon neutral by 2020 – placing his odds of success at 99%. If his country fails, the #1 culprit – in his words – would be the oil industry. Here’s why. President Nasheed also said plans are moving forward for a “sovereign wealth fund” that would allow the Maldives (or possibly a third party acting on behalf of the Maldives) to buy a plot of land in another country, where Maldivians could reside in case the nation ends up underwater, as many scientists predict.

I also asked President Nasheed for his take on climate talks in Durban, South Africa. He says his country – which has more skin in the game than most when it comes to climate change – is used to attending these talks with the odds stacked against it. The agenda at Durban included deciding the future of the Kyoto Protocol. President Nasheed says developing countries need to rethink the “growth=emissions” equation, and the Maldives is an example of a country that’s developing while trying to incorporate renewables along the way. I should mention that the Maldives has the benefit of significant revenue coming in from the luxury tourism industry, which many developing countries don’t. Still, President Nasheed is convinced that other nations of the world will one day have no choice but to follow his example on carbon neutrality. Here, he explains why. He also had this message for the world’s biggest carbon emitters, the United States and China.

___________________

TRANSLATOR’S TAKE

…Fazail Lutfi’s reflections on what has changed on Thulaadhoo since his last visit to this remote Maldivian island two decades ago

__________________________

THE TROUBLE WITH WORDS

On the plane down to Addu, an atoll in the south of the Maldives and site of the 2011 SAARC summit, I was sitting next to my friend and Dhivehi-English translator, Fazail. One of the frustrations we had run into during our reporting on the inhabited islands came down to language. Sometimes, I’d ask what I thought was a simple question like “Do you believe in climate change?” and the translation sounded a lot more complicated than that! So on the plane, I asked Fazail to jot down a few notes on how you say some key phrases in Dhivehi. Here are his answers…

CLIMATE CHANGE: there’s no word/phrase for this

GLOBAL WARMING: duniye idoonuvum – but this actually sounds more like “earth warming.” This does not do justice to the idea of “global warming”. “Earth warming” seems to have less of a connection to earth’s inhabitants than the phrase “global warming”

CLIMATE = there’s no word for this in Dhivehi —-> the closest replacement is “season” (“moosun” in Dhivehi)

GLOBAL = there’s no word for this in Dhivehi —–> the closest replacement is “globe” or “earth” (“dhuniye” in Dhivehi)

WARM = there’s no word for this in Dhivehi —–> the closest replacement is “hot” (“hoon” in Dhivehi)

SEA LEVEL = there’s no word for this in Dhivehi —–> the closest replacement is something like “enlarging ocean” (“kan” in Dhivehi)

___________________________

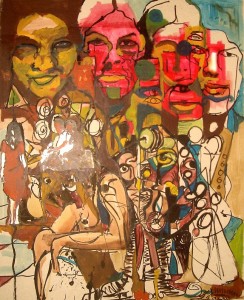

REFLECTIONS OF AN ARTIST

Eagan Badeeu is a Maldivian artist based in the capital, Male’. I asked him to talk about some of his work, which touches on topics including congestion, local politics and the impact of the 2004 tsunami. If you spend enough time on these islands, you start to see how these subjects are connected to the focus of my reporting: climate change. Eagan’s impressions offer a unique window into the Maldivian psyche. Click on the paintings to hear his reflections on each one. (Sound files open in a separate window.) And to see more of Eagan’s art, click here to visit his blog.

___________________________________________________

THULAADHOO – SEVENTEEN HECTARES IN EIGHT DAYS

Baa Atoll in the northwest Maldives consists of about 75 islands. In June, UNESCO designated the atoll a “world biosphere reserve”. We visited Thulhaadhoo, an island that has been expanded through the process of land reclamation. Members of the island council say it grew by seventeen hectares in eight days last year.

My guide, Fazail Lutfi, hadn’t visited Thulaadhoo in more than two decades – he had interesting insights on how it has changed. For one thing, he says it’s a lot greener. People are planting everywhere, in their homes and gardens… even on sidewalks, partly so they don’t have to buy imported vegetables.

Thulaadhoo is known throughout the Maldives for its lacquer work. One craftsman is working on creating a museum devoted to the art. The island’s population is set to grow dramatically, from about 2500 people today to as many as 10,000 in the not-too-distant future. This way, the government can consolidate resources like schools and medical facilities. But locals don’t want their traditions to get lost in the process.

Thulaadhoo once had a vibrant fishing industry, but it’s taken a hit in recent years. The small fish they once used as bait no longer come into the lagoon. They’re not quite sure why. On our trip with a group of fishermen, they used octopus as bait – and only caught about five fish the whole afternoon. Do they believe in climate change? I’ve gotten a wide range of answers on this. Some are very educated about how the actions of industrialized countries affect them. Others are unfamiliar with the terms we use, like “global warming” – there’s no short way to convey that concept in the local language, Dhivehi. But across the board, people notice differences in their environment on a local level – seasons are shifting and there aren’t as many fish as there used to be.

________________________

RETURN TO GURAIDHOO

A week after my first trip to the island of Guraidhoo, I went back, this time without the Chinese delegation in tow. I had a chance to continue interviewing residents concerned about losing their homes to the sea. I wanted to learn more about their predictions, fears, and hopes for the future. Why is it that people can see the water creeping closer to their homes year by year – and still expect that they will spend the rest of their lives on this island?

This is the single most surprising thing about the Maldives so far. People show a remarkable adaptability and an acceptance that nature – and therefore, their lives – will change. Unlike some of the other islands I’ve visited where new stretches of land have been created literally overnight, reclamation hasn’t happened here. Some feel the government (both the previous and current administrations) has failed to do enough to protect them. So they take matters into their own hands, building barriers against the water, which often makes its way into their homes nonetheless.

Erosion has occurred for as long as people can remember. One side of the island is bigger for part of the year. Then, the sands shift to the other side, and the process continues back and forth as the seasons change. The consensus seems to be that erosion has gotten worse since the 2004 tsunami. It gets worse every year. Yet no one here is packing up. Even if they have to move one day (and in their eyes, that day seems far off), they’ve adopted a familiar mantra about the future: If we have to move, we will.

____________________________________________________

HULHUMALE’ – A SIGN OF THE TIMES IN THE MALDIVES

Hulhumale’ is an artificial island, created through reclamation, in which sand is dredged from the ocean floor and used to build new land. Although Hulhumale’ was initially built to relieve congestion in the Maldivian capital, Male’, it’s also a safer bet for residents if the most dire climate change predictions prove true. The U.N. Climate Change Panel projects that sea levels could rise by as much as 90 centimeters by the end of this century. Some scientists say it could be worse. Hulhumale’ is about 2 meters above sea level, making it the highest standing island in the country, according to a spokesperson for the island’s Housing Development Corporation.

________________________________________________________

CLIMATE CHANGE IN THE MALDIVES – AN EVOLVING STORY

This was my first entry from the Maldives:

I got here on Wednesday and by 6 a.m. Thursday, I found myself on a speedboat headed for Guraidhoo Island, a 45-minute ride from the capital, Male’. There, I had an opportunity to talk to local Maldivians about climate change. Here’s what I realized: Although there is serious beach erosion happening, not all the locals attribute this to climate change. In fact, some residents I spoke are unfamiliar with the concept. That surprised me, but it shows a domestic public awareness gap, even in a country that’s become the international poster child for fighting global warming.

It was just one visit – and I’m really looking forward to meeting more people… speaking with them and understanding how they think about their environment. People who live on islands are used to particular ecological patterns that mainlanders like myself haven’t lived with our whole lives. These include erosion, which is well in evidence on Guraidhoo. But although some erosion is normal, they seem to understand that something more serious might be happening. It’s hard not to worry when water is lapping up within feet of your home – especially when it was 30 feet farther away two years ago. One family I visited had little more than a flimsy corrugated metal barrier to guard against the creeping shoreline.

I traveled to the island with a delegation of artists from China, of all places. In my conversations with them, they didn’t want to touch the politics of climate change, but told me that they hope to encourage people back home to adjust their behavior on a “personal level” as a way to help reverse current patterns. [Just in case you were wondering, China emits more carbon dioxide than any other nation.]